Articles

Article Tools

Stats or Metrics

Article

Review Article

Exp Neurobiol 2023; 32(1): 1-7

Published online February 28, 2023

https://doi.org/10.5607/en22037

© The Korean Society for Brain and Neural Sciences

Policy Analysis for Implementing Neuroethics in Korea’s Brain Research Promotion Act

Tae-Woo Kang1,2, Tai-Won Oh2* and Sung-Jin Jeong1*

1Korea Brain Research Institute, Daegu 41062, 2Department of Police, Kyungil University, Gyeongsan 38428, Korea

Correspondence to: *To whom correspondence should be addressed.

Sung-Jin Jeong, TEL: 82-53-980-9410, FAX: 82-53-980-8339

e-mail: sjjeong@kbri.re.kr

Tai-Won Oh, TEL: 82-53-600-5203, FAX: 82-53-600-4020

e-mail: jerryoh@kiu.ac.kr

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

In 1998, Korea implemented the Brain Research Promotion Act (BRPA), a law to revamp the field of neuroscience at the national level. However, despite numerous revisions including the definition and classification of neuroscience and the national plans for the training and education systems, the governance for neuroethics has not been integrated into the Act. The ethical issues raised by neuroscience and neurotechnology remain unchallenged, especially given the focus on the industrial purpose of the technology. In the current study, we analyzed the BRPA revision process by using Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework to determine the problems faced by the process. We propose a new strategy, including neuroethics governance and a national committee, to promote interdisciplinary neuroscience research and strengthen neuroethics in Korea.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Neuroscience, Neuroethics, Brain research promotion act, Kingdon’s multiple streams framework

Body

Neuroscience is evolving rapidly, and converging with engineering, artificial intelligence (AI), nanotechnology, and quantum computing [1]. Technological innovation is taking neuroscience beyond the treatment of and recovery from human defects and cognitive decline [2, 3]. Interdisciplinary research must, therefore, address ethical and legal issues. Existing ethical norms, including bioethics and AI ethics [4], must expand to manage problems that require new perspectives. These technological innovations require us to integrate neuroscience and ethical research [5]. If neuroscience technology enhances the brain, it will lead to important legal and ethical issues, requiring governance to achieve appropriate outcomes and address ethical concerns. This complex and challenging process must flexibly respond to society by using social institutions [6]. South Korea enacted the Brain Research Promotion Act (BRPA) in 1998, recognizing the importance of neuroscience. The BRPA has since been revised to reflect technological and tangible changes as and when required for the issues such as the definition and classification of neuroscience, and strategic plans for the training and education of the next generation. However, a strategy to address the ethical and legal problems associated with neuroscience was excluded, despite several attempts to include it. There is a gap between technology and society, leading to social turmoil and the diminishing of national scientific competitiveness. We analyze the progress and status of the revision of the BRPA by integrating Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework (MSF). We propose an institutionalization of neuroethics legal policy.

OVERVIEW OF THE BRPA REVISIONS

The Framework Act on Science and Technology (FAST) is the highest law covering science and technology policy in Korea (The department in charge is the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT)). The Biotechnology Promotion Act (BPA) is a subordinate statute of FAST and provides the basis for the formulation of a comprehensive basic plan for the life sciences and biotechnology at the national level. The Basic Plan for Neuroscience Research has been established under the BRPA, which is a part of the Basic Plan for the Development of Biotechnology as a subordinate statute of the BPA (Table 1). As such, policy on neuroscience is perceived as a sub-field of biotechnology. The Korean government released the Third Basic Plan for Biotechnology Development in September 2017 [7]. Ethical, legal, and social implications of research on new bioethics were included in the plan. However, the plan does not actively reflect the long-term goals and strategies of the other areas of innovative technologies, such as neurotechnology involving the brain-computer interface. In the past, technology developed slowly, affecting our lives gradually; thus, it was possible to make regulatory-oriented laws and provide passive legislation to protect humans and property.

However, it is essential to implement legislation before any technology is introduced in neuroscience due to the fast pace of innovation. Laws must support society to create new and desirable values in a safe system [8]. Additionally, social constituents must form a fully deliberated and socially acceptable legal order. To ensure the safe development of neurotechnology, the views of the public and private sectors working in neuroscience must be considered in BRPA revision. This can lead the national efforts to proactively respond to future innovations in technology, for example, the establishment of new governance as an initial step.

Since the law was enacted in 1998, six major amendments have been implemented, excluding minor changes. The members of the National Assembly proposed a bill in 2018 to amend the BRPA to revise the regulation of brain research (Box 1) [9]. This revision included two major items: the creation of a Brain Bank to enable researchers to obtain brain resources, and the governance of neuroethics. The regulation of the Brain Bank has finally been adopted by the National Assembly through several legislative changes. Regarding neuroethics, the item proposed in the BRPA amendment was to form the National Neuroethics Commission as a national committee to respond to the legal and ethical issues raised by the developments and applications of neurotechnology. In addition, the item would have allowed the MSIT to designate the Neuroethics Policy Center to perform neuroethics research. However, this revision was constantly delayed and ultimately not implemented.

| Box 1. BRPA amendments by members of the national assembly in 2018 (summary) |

| 1. Brain Bank: Clarify the definition of brain research resources and brain banks. Prepare standards for securing, selling, supplying, preserving, and disposing of brain research resources. In addition, the management and permission standards for brain resources and brain banks are prepared. |

| 2. Governance for neuroethics |

| • Neuroethics Committee: The Neuroethics Committee shall be established under MSIT to deliberate on the development of brain research and the associated science and technology. This national-level committee on neuroethics may be established to review ethical, social, and legal issues arising from the development of neurotechnology and its application. |

| • Policy Center for Neuroethics: The MSIT may designate related institutions and organizations as the Policy Center for Neuroethics to conduct policy research, education, and performance diffusion related to neuroethics. |

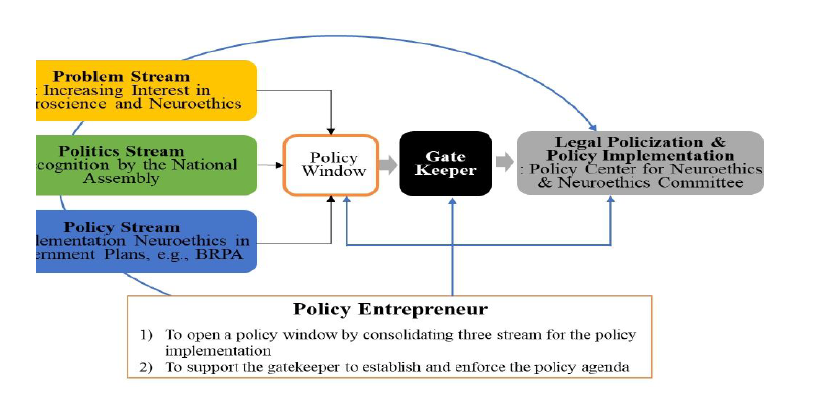

KINGDON’S MULTIPLE STREAMS FRAMEWORK

There are a wide variety of new issues in any society; however, not all of them are included in the society’s legal policy. Some of these issues are highlighted by the media as social issues leading to changes in legal policy, although this is not common. It is difficult for most issues to be integrated into policy and law. According to Kingdon’s MSF [10], the stages of policy formulation are: formation, implementation, and evaluation over time. In policy formation, the circumstances surrounding policies, regime changes, and external shocks are important factors (Fig. 1).

In addition, unexpected accidents or events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can be decisive opportunities to change existing policies or formulate new one [11, 12]. Policies in science and technology play important roles in solving current problems and developing future competencies by focusing on agenda that arises from social and public issues. Environmental and policy changes may create tangible results and set the ground for strategies used by politicians to secure political support [13].

However, this kind of policy formation occurs infrequently for science and technology. According to the MSF, policy formation and development are derived from making realistic policy decisions, changing governance norms, and analyzing factors, which affect the development of detailed programs [14]. The MSF describes a series of processes wherein a policy window is opened and three parallel currents—problematic elements, political elements, and policy factors—are selected as policy agendas according to the role of the policy entrepreneurs [15, 16]. In the MSF policy process, the role of policy entrepreneurs is an important factor, along with policy formation (Fig. 1). Policy entrepreneurs strive to adopt preferred policies by opening a policy window—through continuous interviews and discussions with stakeholders, planning and drafting proposals, reaching out to those in critical positions who influence policy decisions, and drafting legislation. Policy entrepreneurs may include various members of society, including expert groups, interest groups, bureaucrats, media, and academia [17]. To collect the opinions of several participants and institutionalize them into legal policies, it is necessary to balance the feasibility of the policies in terms of the future value of science and technology, social benefits, and the relationship between the policymakers [18]. Therefore, policy entrepreneurs must possess professional knowledge and social insights. Without the dedicated efforts of policy entrepreneurs, the three elements of MSF may not be strongly combined: If the policy window is not opened, it will not lead to policy outcomes such as legislation [19].

BRPA ANALYSIS WITH KMSF MODEL

MSF analysis for the revision process of the BRPA

The main process of the BRPA revision in the MSF model is as follows:

- Problem stream: Increasing domestic and international interest in neuroscience and neuroethics related to AI and neurotechnology.

- Political stream: Recognition of the significance of neuroscience and neuroethics by the National Assembly.

- Policy stream: Facilitating reflection on government plans such as the Third Basic Plan for Brain Research and Korea Brain Initiative.

The Korea Brain Initiative was launched in 2017 [20, 21], and the new R&D strategy for brain research was released by the MSIT in 2018. These events opened the policy window. Before this, the members of the National Assembly collaborated with the Korean Brain Research Institute (KBRI) to organize a special meeting in February 2018 to gather information from national brain projects—the BRAIN Initiative for the US, the Human Brain Project for the EU and Brain/MINDS for Japan—to discuss the governance and issues associated with neuroethics. This meeting coincidentally opened a policy window at the political stream level. Simultaneously, the MSIT prepared the Third Basic Plan for Promoting Brain Research and intended to include governance for neuroethics in this plan. The main contents of the plan were designating the establishment of the Brain Neuroethics Committee and the Center for Neuroethics Policy. Since 2017, the KBRI has been working with the MSIT, universities, and research institutions to integrate neuroethics into policy [21]. Meanwhile, the MSIT supported the 10th World Congress of the International Brain Research Organization (IBRO), which was held in Daegu, Korea, in 2019. The IBRO World Congress was hosted by the KBRI and the Korean Society for Brain and Neuroscience and included neuroethics programs such as a neuroethics session and the Annual Meeting of the Global Neuroethics Summit (GNS), one of the working groups of the International Brain Initiative. Students, researchers, and the public participated in the IBRO World Congress, aiming to understand the present status and future of neuroscience research and neuroethics. Within the MSF model, the KBRI served as a policy entrepreneur in policy formation by communicating with the stakeholders of the framework’s three streams. Policy problems, political currents, and the flow of policy alternatives seemed to open a policy window for the legalization of neuroethics. However, even when the policy window was opened through various events (problem factors) and politicians and policymakers’ interest in revising the agenda grew (political and policy factors), no major topics or issues raised the interest of the public or decision-makers further. In addition to the three factors of the MSF model, we recognized that the final policy output remained invisible because it was unclear who should ideally play a key role in the policy flow as a policy mediator to establish and enforce the policy. The role of universities and research institutes as neuroscience experts has been emphasized; however, they have not been able to lead and analyze the issues to achieve social consensus as policy mediators [22].

Revision process of the BRPA for the MSF and gatekeeper theory

To integrate special issues into national policy, we considered the concept of a “gatekeeper” in this study (Fig. 2). The gatekeeper has the authority to incorporate an agenda in the revision process and plays a critical role in the policymaking process (Fig. 2) [23]. Presidents, members of the National Assembly, and government officials act as the “gatekeepers” in deciding whether to reflect the policy agenda in the policy process and as “decision makers” for institutionalizing the policy agenda into legal policy. However, most of them tend to work on agendas that secure their interests, such as elections and the concentration of power [24, 25]. In other words, it is difficult to ensure the accountability of decision-makers for their public duties. If a gatekeeper raises an issue that does not interest the decision-makers, they are likely to avoid public accountability because unexpected backlash or controversy may be detrimental to them [26]. Therefore, most groups of professionals who take on the role of policy entrepreneur must consider inclusivity and diversity. Policy entrepreneurs need to—formally and informally—form prior opinion exchanges and cooperative relationships with the gatekeepers who establish and enforce the policy so that the gatekeepers can determine the appropriate policy agendas. In addition, policy entrepreneurs serve as a support for the gatekeeper to achieve the desired policy output throughout the entire policy process [27, 28].

Policy flows are the process of deriving optimal planning from complex interests within society. There are limits to complementing value judgment issues that can contribute greatly to the welfare of society. In addition, expert groups perceive political compromises and value judgments as elements to be rejected in scientific research; therefore, policy flows may be slightly removed from the reality [29]. When a policy window opens, the gatekeeper can select the agenda proposed by the policy entrepreneur to create a legal policy. Policy entrepreneurs play a leading role in influencing the selection and decision of the gatekeeper’s policy agenda [30]. Therefore, neuroscientists and professional groups are crucial to the institutionalization and dissemination of neuroethics for legal policy governance. In addition, it is necessary to consider a method for verifying the objectivity and publicity of policy entrepreneurs through consultation with other stakeholders [31]. In a mixed model of the MSF and the gatekeeper, policy entrepreneurs should:

- Try to reflect the opinions of experts and the public in the policy process

- Ensure that legal policies are appropriately disseminated in society

- Communicate with the political side to develop the policy agenda

- Support the gatekeepers to establish and enforce the policy

Policy entrepreneurs must strengthen the role of “policy mediators” so that they can implement the aforementioned roles efficiently [26].

DISCUSSION

BRPA needs to be revised to promote neuroscience research. Furthermore, integration of neuroethics into the BRPA is imperative for scientists to conduct their research responsibly and safely. In this study, we analyzed BRPA revision process using the MSF model and found that policy entrepreneurs were required to be policy mediators to communicate with the gatekeepers to integrate neuroethics into the BRPA. It is ideal for scientific societies and institutes to lead this agenda as policy entrepreneurs. Without such policy entrepreneurs, the exclusive legal policies of minority interest groups and bureaucrats will shape the agenda to be implemented in the legislation process. However, scientific societies and institutes have their missions and functions in terms of scientific activities. Therefore, we propose the establishment of the Policy Center for Neuroethics to play a key role as both policy entrepreneur and intermediator in managing issues, setting agendas, extracting policy factors, and supporting the gatekeeper for legislation. In addition to policy entrepreneurs, the participation and input of the public are critical for the BRPA revision process; citizen participation ensures that sustainable legislation and revision of the law are prioritized [32]. To maximize the integration of neuroethics into the BRPA, a communication system must be established for the public to share their opinions. Accordingly, the governance would be able to enhance communication among the public, experts, and politicians. The establishment of new governance is not simply about extending the scope of the public sector and promoting the interests of scientific societies and institutes [33]. Therefore, we propose a National Neuroethics Committee that will reflect and integrate the public’s interests in the legislative process as another intermediator to communicate with the gatekeepers during the revision process. In addition, the neuroethics committee determines and reflects policy agenda as one of the gatekeepers, in consideration of diversity and transparency, to promote knowledge sharing and reduce the conflicts of interest among stakeholders. To enhance multidisciplinary and pluralistic dialogue, it is ideal to establish the National Neuroethics Committee as an independent and multidisciplinary body. The roles of governance such as the Policy Center for Neuroethics and Neuroethics Committee must be designated by law to strengthen their official status. Neuroethics urges us to reflect on sociocultural factors, address social issues, and prevent ethical issues related to both basic and clinical neuroscience and policy-making (Box 2) [34]. For example, if we face events such as brain transplantation in the future, the Policy Center for Neuroethics and Neuroethics Committee will assess the scientific and technological feasibility to evaluate the current state of the science and technology of brain transplantation, including the risks and benefits at the first step. They will then examine the ethical implications of the technology—including those related to personal identity, autonomy, and dignity—to provide the appropriate recommendations and guidelines for responsible use (for clinical practice as well as research). In addition, they will provide education and information about the ethical issues related to brain transplantation to several stakeholders (including the public) and will monitor the implementation of the guidelines and evaluate the effectiveness over time.

| Box 2. The mission of the Policy Center for Neuroethics and Neuroethics Committee |

| • Policy Center for Neuroethics: 1) In line with social changes caused by the development of convergence technology, practical implementation platform functions, such as policy planning, planning as well as support for both functions of "the ethics of neuroscience" and "the neuroscience of ethics" should be performed. 2) Similar to AI ethics, the industrialization of neuroscience will cause problems beyond the limits of jurisdiction. International ethics discussions are essential to solve these problems. It is necessary to carry out national ethical forums and consultative functions to establish global norms and ethical standards through active consultation with international organizations. |

| • Neuroethics Committee: 1) Future science and technology developments are expected to generate more results by converging with heterogeneous technologies such as Data and AI based on neuroscience. 2) Neuroethics requires more interdisciplinary research with existing ethics frames such as those for AI, metaverse, mechanics, and biological fields. 3) The Neuroethics Committee needs to establish its status and play a role as a state organization for future convergence, universal ethics, and research ethics in neuroscience such as pre-technical and efficacy evaluations. |

In this study, we focused on the implementation of neuroscience in the legal system by analyzing the MFS model. However, this model can be also applied to other fields and multidisciplinary areas (such as neuroscience and AI) by considering the three streams—problem, policy, and politics. The problem stream involves identifying and defining the challenges and opportunities associated with the interaction of neuroscience and AI. For example, ethical considerations can be raised by the integration of AI and brain function—such as brain-computer interfaces (BCI) that interpret large amounts of brain data—with questions about privacy, security, bias, accuracy, and so on. The policy streams explore the various approaches and solutions processed to address the challenges and opportunities identified in the problem stream. This is not the challenging aspect because most stakeholders are interested in AI technology and agree that governance must manage the technique. For the politics stream, there are the various factors and stakeholders that influence the development and implementation of policies and solutions in the policy stream. Therefore, the MFS can provide a comprehensive and systemic way to understand and analyze complex and dynamic multidisciplinary techniques, such as combining neuroscience with AI, to benefit the future society.

As ethical issues have been raised by neurotechnology at the global level, the international community insists on responsible research in neuroscience and demands accountability for sensitive research on the human brain. For example, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been involved in the integration of neuroethics into international policies for the development of neuroscience. Recently, the organization has published two articles titled “Neurotechnology and Society: Strengthening Responsible Innovation in Brain Science”[35] and “Responsible Innovation in Neurotechnology” [36]. The OECD emphasizes the establishment of governance in each country and the establishment of a global cooperative system to facilitate responsible research innovations and advance neuroscience and technology [37]. Further, the GNS suggests five neuroethics questions that scientists must consider during their scientific endeavors [38]. Neuroscience and technology will continue to develop; thus, legal and policy efforts should be emphasized to respond systematically to both expected and unexpected problems by reconstructing the existing laws [36]. For efficient legislation, including the revision of the BRPA, it is crucial to develop platforms such as the National Neuroethics Committee and the Policy Center for Neuroethics, which would enable all stakeholders to communicate and be involved in the processes of legislation and BRPA revision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Kyungjin Kim (Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science & Technology, Daegu, Korea) for reading the manuscript and providing helpful comments. This project was supported by the Neuroethics Research Project of the National Research Foundation of Korea (2019M3E5D2A02064496).

Figures

Tables

Law and strategy pans for science and technology in Korea

| Law | Framework act on science & technology | Biotechnology development act | Brain research promotion act |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government strategic plan | 1. Strategic plans for science and technology 2. Mid and long-term strategies for national R&D | Basic plan for biotechnology development | Strategic plans to facilitate brain research |

| Organization | Presidential advisory council on science and technology | Council for biotechnology policy | Working committee for brain research |

References

- Blue C (2021) Could quantum computing revolutionize our study of human cognition?: quantum computers may bring enormous advances to brain research [Internet]. Association for Psychological Science, Washington, D.C.

Available from: https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/quantum-leap - Canton J (2012) Toward our neurofuture: challenges, risks, and opportunities. In: Neurotechnology: premises, potential, and problems (Giordano J, ed), pp xiii-xvii. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL

- Marx V (2021) Biology begins to tangle with quantum computing. Nat Methods 18:715-719

- Miah A (2011) Ethics issues raised by human enhancement. In: Values and ethics for the 21st century (BBVA, ed). BBVA, Madrid

- de Oliveira N (2016) On ritalin, adderall, and cognitive enhancement: metaethics, bioethics, neuroethics 15:343-368

- Shook JR, Giordano J (2019) Ethical contexts for the future of neuroethics. AJOB Neurosci 10:134-136

- Ministry of Science and ICT (2017) The third basic plan for biotechnology development (bio-economic innovation strategy 2025). pp 1-417. Ministry of Science and ICT, Gwacheon

- Saenko N, Voronkova O, Volk M, Voroshilova O (2019) The social responsibility of a scientist: the philosophical aspect of contemporary discussions. JSSER 10:332-345

- Ministry of Science and ICT (2018) The third basic plan for the promotion of brain research. pp 1-68. Ministry of Science and ICT, Gwacheon

- Kingdon JW (2011) Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd ed. pp 251-257. Longman, Boston

- Giese KK (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019's shake-up of telehealth policy: application of Kingdon's multiple streams framework. J Nurse Pract 16:768-770

- Hoefer R (2022) The multiple streams framework: understanding and applying the problems, policies, and politics approach. J Policy Pract Res 3:1-5

- Holdsworth D (2002) Science, politics and science policy in Canada: steps towards a renewed critical inquiry. J Can Stud 37:14-32

- Béland D, Howlett M (2016) The role and impact of the multiple-streams approach in comparative policy analysis. J Comp Policy Anal 18:221-227

- Cairney P, Jones MD (2016) Kingdon's multiple streams approach: what is the empirical impact of this universal theory?. Policy Stud J 44:37-58

- Widyatama B (2018) Applying Kingdon's multiple streams framework in the establishment of law no.13 of 2012 concerning the privilege of Yogyakarta special region. J Gov Civil Soc 2:1-18

- Duke K, Herring R, Thickett A, Thom B (2013) Substitution treatment in the era of "recovery": an analysis of stakeholder roles and policy windows in Britain. Subst Use Misuse 48:966-976

- Cairney P (2018) Three habits of successful policy entrepreneurs. Policy Polit 46:199-215

- Stanifer SR, Hahn EJ (2020) Analysis of radon awareness and disclosure policy in Kentucky: applying Kingdon's multiple streams framework. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 21:132-139

- Jeong SJ, Lee H, Hur EM, Choe Y, Koo JW, Rah JC, Lee KJ, Lim HH, Sun W, Moon C, Kim K (2016) Korea brain initiative: integration and control of brain functions. Neuron 92:607-611

- Jeong SJ, Lee IY, Jun BO, Ryu YJ, Sohn JW, Kim SP, Woo CW, Koo JW, Cho IJ, Oh U, Kim K, Suh PG (2019) Korea brain initiative: emerging issues and institutionalization of neuroethics. Neuron 101:390-393

- Howlett M, McConnell A, Perl A (2016) Kingdon à la carte: a new recipe for mixing stages, cycles, soups and streams. In: Decision-making under ambiguity and time constraints: assessing the multiple-streams framework (Zohlnhöfer R, Rüb F, eds), pp 73-89. ECPR Press, Colchester

- Anderson W (1953) The political system: an inquiry into the state of political science. By David Easton. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1953. Pp. xxiii, 320. $5.00.). Am Polit Sci Rev 47:862-865

- Stone D (2009) Rapid knowledge: 'bridging research and policy' at the overseas development institute. Public Admin Dev 29:303-315

- Kay L (2019) Guardians of research: negotiating the strata of gatekeepers in research with vulnerable participants. Practice 1:37-52

- Sovacool BK, Turnheim B, Martiskainen M, Brown D, Kivimaa P (2020) Guides or gatekeepers? Incumbent-oriented transition intermediaries in a low-carbon era. Energy Res Soc Sci 66:101490

- Bachrach P, Baratz MS (1963) Decisions and nondecisions: an analytical framework. Am Polit Sci Rev 57:632-642

- Eckersley P, Lakoma K (2022) Straddling multiple streams: focusing events, policy entrepreneurs and problem brokers in the governance of English fire and rescue services. Policy Stud 43:1001-1020

- Head BW, Alford J (2015) Wicked problems: implications for public policy and management. Adm Soc 47:711-739

- Van Loo R (2020) The new gatekeepers: private firms as public enforcers. Va Law Rev 106:467-522

- Bagga-Gupta S, Dahlberg GM, Almén L (2022) Gatekeepers and gatekeeping. In: Accessibility denied. Understanding inaccessibility and everyday resistance to inclusion for persons with disabilities (Egard H, Hansson K, Wästerfors D, eds), pp 90-106. Routledge, Abingdon

- Sabatier PA (1991) Toward better theories of the policy process. Polit Sci Polit 24:147-156

- Reynolds B, Seeger MW (2005) Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. J Health Commun 10:43-55

- Liu EY (2018) Neurodiversity, neuroethics, and the autism spectrum. In: The Routledge handbook of neuroethics (Johnson LSM, Rommelfanger KS, eds), pp 394-411. Routledge, New York, NY

- Garden H, Bowman DM, Haesler S, Winickoff DE (2016) Neurotechnology and society: strengthening responsible innovation in brain science. Neuron 92:642-646

- OECD (2019) OECD recommendation on responsible innovation in neurotechnology. OECD, Paris

- International Brain Initiative (2020) International Brain Initiative: an innovative framework for coordinated global brain research efforts. Neuron 105:212-216

- Rommelfanger KS, Jeong SJ, Ema A, Fukushi T, Kasai K, Ramos KM, Salles A, Singh I (2018) Neuroethics questions to guide ethical research in the international brain initiatives. Neuron 100:19-36