Articles

Article Tools

Supplementary

Stats or Metrics

Article

Original Article

Exp Neurobiol 2023; 32(3): 181-194

Published online June 30, 2023

https://doi.org/10.5607/en23001

© The Korean Society for Brain and Neural Sciences

An Automated Cell Detection Method for TH-positive Dopaminergic Neurons in a Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease Using Convolutional Neural Networks

Doyun Kim1†, Myeong Seong Bak2,3†, Haney Park2,3, In Seon Baek2, Geehoon Chung1, Jae Hyun Park4, Sora Ahn5, Seon-Young Park1, Hyunsu Bae1, Hi-Joon Park5 and Sun Kwang Kim1,2,4*

1Department of Physiology, College of Korean Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, 2Department of Science in Korean Medicine, Graduate School, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, 3Department of AI and Data Analysis, Neurogrin Inc., Seoul 02455, 4Department of East-West Medicine, Graduate School, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, 5Acupuncture & Meridian Science Research Center, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea

Correspondence to: *To whom correspondence should be addressed.

TEL: 82-2-961-0323, FAX: 82-2-961-0333

e-mail: skkim77@khu.ac.kr

†These authors contributed equally to this article.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Quantification of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive neurons is essential for the preclinical study of Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, manual analysis of immunohistochemical (IHC) images is labor-intensive and has less reproducibility due to the lack of objectivity. Therefore, several automated methods of IHC image analysis have been proposed, although they have limitations of low accuracy and difficulties in practical use. Here, we developed a convolutional neural network-based machine learning algorithm for TH+ cell counting. The developed analytical tool showed higher accuracy than the conventional methods and could be used under diverse experimental conditions of image staining intensity, brightness, and contrast. Our automated cell detection algorithm is available for free and has an intelligible graphical user interface for cell counting to assist practical applications. Overall, we expect that the proposed TH+ cell counting tool will promote preclinical PD research by saving time and enabling objective analysis of IHC images.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Mice, Dopaminergic neurons, Deep learning, Neural networks, Cell count

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc). Symptoms of PD primarily include movement-related and non-motor indications [1]. Specifically, movement-related symptoms include tremor, postural instability, stiffness, and bradykinesia, while additional non-motor symptoms include pain, depression, cognitive deficit, psychiatric disease, obstipation, and urinary incontinence [2, 3]. These symptoms significantly deteriorate the quality of life of patients and can even lead to death [4]. Despite extensive studies of PD, the incidence of the disease continues to rise and has been estimated to range between 8 and 18 per 100,000 person-years, be higher in men than in women, and increase with age [5].

Animal models of PD are important tools to understand its etiology and develop treatments. Chemical agents that selectively destroy catecholaminergic systems, such as 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), 6-hydroxydopamine, methamphetamine, and reserpine, have been used to develop rodent models of PD [6]. These agents allow rapid, brain-specific modulation, which is advantageous for research. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis using protein markers of dopaminergic neurons has been widely applied to validate the animal models of PD [7]. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) is an enzyme that synthesizes L-dihydroxyphenylalanine, a precursor of dopamine; therefore, quantification of TH+ neurons in SNc is currently considered the gold standard for evaluating rodent models of PD [8].

Diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining is the most frequently used method to determine the proportion of TH+ cells in brain tissues [9, 10]. DAB reacts with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to produce brown coloration [11]. Although DAB staining is characterized by high sensitivity [12], the staining intensity varies with the enzymatic activity of HRP. In addition, the staining intensity is strongly affected by temperature, reaction time, and HRP substrate concentration [13]. Moreover, because of high cell density in the SNc region, the signal-to-noise ratio of IHC-DAB staining results is remarkably low [14]. Therefore, TH+ cell detection for the verification of PD models is typically performed manually, which is labor intensive and time consuming. Finally, manual analysis involves human bias and subjectivity, leading to low reproducibility and high inaccuracy. Thus, an automatic cell detection method is required for faster and more objective analysis.

Development of target detection algorithms, such as Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) [15, 16], difference of Gaussian (DoG) [17-19], and determinant of Hessian (DoH) [15, 20], has enabled automatic object detection on biological images [21-23]. In addition, many image analysis tools, such as ImageJ (IJ), CellProfiler (CP), ilastik (Ila), and QuPath (QP), which do not require specific skills in programming, have been developed [24] and actively utilized in recent years [25-29]. Despite these advances, however, the quantification of TH+ neurons in most studies on PD remains manual, perhaps because using these algorithms and tools still requires substantial manual effort [24], rendering them inefficient. Furthermore, these methods are inadequate for detecting objects with intricate factors, such as size and shape irregularity, weak boundaries, and high density.

Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are computational models based on the features of biological neurons with multiple hidden layers, and these models are specialized in the detection, segmentation, and recognition of objects and regions on images [30-32]. With advances in CNNs, automatic object detection on pathological images, which are challenging to analyze, has been successfully implemented in various fields [33-35]. Unsurprisingly, several CNN-based detection methods for rodent models of PD have been proposed [36, 37]. However, these methods are riddled with difficulties in practical application. For instance, these models lack a free accessible user interface. In addition, they are not designed with emphasis on resolving challenges due to the complex features of images, including unclear boundaries of neurons and noises in the background [36].

In the present study, we proposed a CNN-based supervised learning model for detecting TH+ dopamine neurons in rodent SNc. The proposed model is established based on Python, a free platform to increase its accessibility. After implementing the model, we validated its performance against manual scoring results obtained by two human observers. Additionally, we realized an intelligible graphical user interface (GUI) to apply the model effortlessly and cover the conditions and requirements of individual researchers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6N mice were 8-week-old at the start of the experiments. The mice were housed at a constant temperature (23±1℃) and humidity (60%) under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the Kyung Hee University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (KHUASP (SE) 20-678) and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Drug treatment

To establish an animal model of PD, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 30 mg/kg/day of MPTP for 5 consecutive days [10]. The control group was injected with the same volume of saline for 5 consecutive days.

IHC analysis

The mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and then perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) through the left ventricle, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4℃ and then dehydrated in a 30% sucrose solution until the brains subsided. Thereafter, the brains were cut into 40 μm coronal sections containing the SNc region using a cryosection (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). To ensure unbiased sampling, every third of the brain slices was obtained between AP -3.08 and -3.64 mm from bregma, resulting in a total of four sections gathered from a hemisphere [38, 39]. Although stereological methods have been established for PD diagnosis, most preclinical PD studies have used planar IHC images for the detection and counting of TH+ cells [40-42]. Therefore, we developed a deep learning model for automated quantification using planar IHC images.

The brain sections were washed with PBS and incubated with 1% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were washed again with PBS and blocked in a solution containing 3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h. Next, the sections were incubated with anti-TH antibody (1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 4℃ for 72 h. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1 h. Thereafter, the sections were incubated with avidin-biotinylated peroxidase complex (Vectastain Elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) solution for 1 h. The brain sections were rewashed with PBS and stained with DAB (DAB Substrate Kit, Peroxidase, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for approximately 40 s. The stained sections were mounted on slide glasses coated with aminosilane and dehydrated in 70%, 80%, 90%, and absolute ethanol. The slides were cleared with xylene, and coverslips were placed using a Permount solution. Histological images of the SNc region were obtained under a bright-field microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Microscopy

Images of the stained SNc sections were captured using a digital camera (Pixit FHD One, Nahwoo Trading Co. Suwon, South Korea) connected to a bright-field microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 4× objective lens (NA 0.10, WD 30 mm, CFI Plan Achromat 4×, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Each original image was saved with a .jpg extension of approximately 1.4 MB and had the resolution of 2592×1944 pixels with 24-bit RGB channels.

Datasets

In this present study, there are three datasets created by different IHC staining protocols from different laboratories.

1. The dataset used for training and cross-validation of the model contained 96 IHC images with varying brightness and staining intensities. On average, 100.8 cells were counted in 52 images from the control group, while 78.8 cells were counted in 44 images from the MPTP group. A total of 8,496 cells were manually labeled (see Table 1). These images were captured at a magnification of 40× and had a spatial resolution of 0.924 μm per pixel.

2. The second dataset was also used to test the model’s generalization ability. In this dataset, an average of 120.7 cells were counted in 20 images. The images were taken at a magnification of 40× with a spatial resolution of 0.881 μm per pixel.

3. The third dataset was used solely to test the model’s generalization ability. On average, 141.2 cells were counted in 32 images. These images were captured at a magnification of 100× and had a spatial resolution of 0.369 μm per pixel.

Manual scoring criteria for TH+ cell

TH+ dopaminergic neurons are round somatic cells possessing 2~4 dendritic trunks, with an average diameter of 12~15 μm [43]. Using the IJ program, the number of circular and dark-colored cells within the SNc region was manually counted. Cells with any of the following characteristics were excluded from counting: (1) if the cell was outside the SNc region, (2) if it was not dark enough, or (3) if it was too elongated. The SNc region was determined with reference to the Allen Brain Atlas.

Image preprocessing

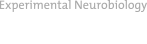

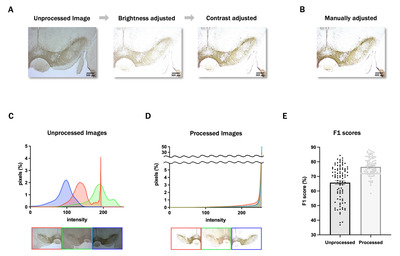

Even for manual scoring, adjusting the image brightness and contrast is essential to distinguish the cells more clearly. We established a code automating this process to enable more rapid and consistent analysis. First, the standard deviation (σ), mean (μ), and mode of the intensity of each image were calculated. Then, we used the values and averages of each to set ranges. Finally, using PIL.ImageEnhance, the brightness and contrast of each image were adjusted to have an intensity distribution (IDB) within the ranges (see Fig. 1A).

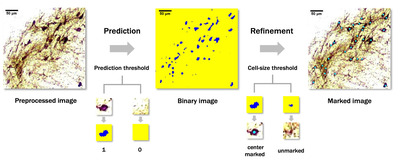

Refinement and quantification

Cell region detection was performed by coloring the center pixel of the patch where a cell is likely to exist. Then, the area of each blob formed by the colored center pixels was calculated using cv2.findContours, and only blobs with the size of the threshold set by users or more were retained as the cell candidates. Finally, markers were labeled at the center of each candidate, and an annotated image was produced by adding the markers to the original processed image with the markers. The number of markers was presented as the total cell count (see Fig. 1C).

Evaluation and statistical analysis of model performance

The performance of the proposed algorithm was evaluated by calculating the averages of the recall, precision, and F1 score of each image. The metrics were defined as follows. TP, FN, and FP denote true positive, false negative, and false positive, respectively.

We compared the performance of the proposed model with that of the other methods by calculating the F1 score of three traditional target detection methods: LoG, DoG, and DoH. Then, we analyzed the concordance between manual counting and algorithm-predicted results through linear regression and the distribution of counting results between the control (saline) and MPTP groups in each method. Finally, we measured the time required by the model to quantify cells.

Cross-validation

Cross-validation is a standard statistical method of evaluating the performance and generalizability of an algorithm by dividing the datasets into training and validation sets. Since the goal is to predict a new IHC image, we divided the cross-validation set based on the image. A total of 96 images were divided into 20 cross-validation sets, and 4 to 5 test images were assigned to each test set.

GUI implementation

The proposed GUI was programmed in Python using PyQt5, a cross-platform GUI library. In addition, we used libraries such as, sys, cv2, imutils, time, csv, keyboard, and Numpy, for developing GUI to enable users to utilize the proposed algorithm. The GUI was designed to contain the automatic image preprocessing code and proposed CNN model. The input is an IHC image. As output, with total cell counts, the cell region binary image and predicted center-marked image are provided as savable image files. Additionally, center coordinates of the detected cell bodies are provided as a CSV file (see Fig. 1C).

RESULTS

Model design and implementation

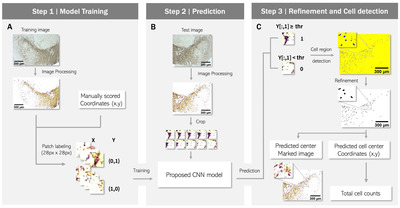

To develop a method for cell detection and counting, we designed a supervised learning model that divides the entire image into small crops and outputs the presence or absence of a cell in the center pixel of each crop (Fig. 1). The datasets were obtained from a total of 96 IHC images from 13 mice (Table 1, 2). The architecture of the deep learning model is shown in Fig. 2 and Table 3. We used human-annotated pixels as the ground truth for our model. This strategy offers the advantage of easily obtaining training data compared to segmentation, which requires the task of drawing an area. However, using a single pixel as the ground truth can introduce noise. For example, even if one error occurs among approximately a million negative pixels, it may be classified as a false positive. To address this issue, we assigned additional positive labels to pixels within a 6-pixel distance from the positively labeled pixel. With this modification, the final output had large clusters near the manual annotation positions, improving performance by filtering noise through size thresholding in what we named the “refinement phase.”

Furthermore, the selection of negative labels should be considered. There are numerous negative pixels in an IHC image. We acquired patches measuring 28×28 pixels from each image using coordinates of markers that human observers manually placed at the center of cell bodies. The number of patches in an image is equal to the number of pixels. In our analysis pipeline, there is a process of filtering out false positives based on the size of the blob, which is a cluster of detected pixels. To maximize this filtering effect, rather than simply select a single cell-positive patch at a manually labeled coordinate, we selected additional cell-positive patches as pixels within a Euclidean distance of 6 pixels centered on that pixel. As a result, the single manually selected coordinate was expanded to 121. To select cell-negative patches, we carefully established conditions. Firstly, to clearly distinguish the boundary from the cell-positive patch, we extracted cell-negative patches from the vicinity of positive patches. Specifically, a cell-negative patch was randomly extracted from an area at least 6 pixels away but within 30 pixels from the center coordinates of the cell-positive patches. The number of cell-negative patches corresponding to this condition was nearly 3.2 times that of cell-positive patches. Additional cell-negative patches were randomly extracted from the entire area of the image at least 6 pixels away from the cell-positive patches. The number of patches for this condition was 20% of that of the cell-positive patches.

In addition, we optimized the hyperparameters of the deep learning model, such as patch size and the number of parameters, through trial and error. We also normalized the scale of all patches by dividing each patch by its mean value, resulting in a mean value of 1 for all patches. On average, we selected 53,639 cell-negative and 15,928 cell-positive patches from an image. After extracting the patches, we annotated the cell-positive and cell-negative patches as [0,1] and [1,0], respectively. This was done to prepare the data for use in a deep learning classification model in Python. The annotations serve as the target values (y-values) for the model to predict during training.

Image preprocessing

IHC images used in the present study presented different brightness and contrast values (Fig. 3C); as such, most images presented low brightness and contrast values, rendering the identification of cell body boundaries difficult. Furthermore, users are expected to apply the model on their own IHC images generated under different conditions. Therefore, we devised a method to automatically adjust the brightness and contrast of the image such that the cell bodies in it with any features can be detected much more accurately. We conducted a quantitative analysis to assess the similarity of image intensity in our dataset by the proposed automatic image preprocessing method. The average intensity value of all extracted image patches was calculated for each image before and after preprocessing. The percentage change in values for each group from their mean was then calculated, with the sign of the percentages of increase and decrease treated as absolute values. Our results showed that before image preprocessing, each image had a variation of 10% from their mean, which decreased to 7.2% after preprocessing. A paired Z-test was performed to check for statistical significance, yielding a p value of 0.0011. This indicates that image preprocessing significantly increases the similarity of image intensity (Fig. 3D). Further, to verify the effectiveness of image preprocessing, we compared the F1 scores for cell detection with and without preprocessing using a cross-validation method. The results (Fig. 3E) showed that the F1 score increased from 0.65 to 0.76, confirming that the image preprocessing step significantly improves cell detection analysis.

Cell detection

The proposed cell detection process was completed in two phases: (1) cell region prediction and binarization phase and (2) refinement and blob detection phase. Following cell region prediction and binarization, the binary images showing areas likely to be occupied by cells were formed (Fig. 4). These images also contained some noises, which could hardly be judged as areas of cells. In refinement and blob detection phase, such noises were eliminated, and images with well-positioned markers at the center of the cell bodies were obtained (Fig. 1C, 4).

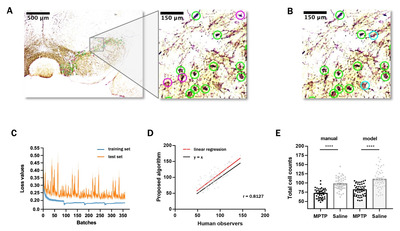

Fig. 5A presents the detection results of an image using our machine learning algorithm and Fig. 5B presents the manual scoring results of the same image, indicating a substantial match between them. According to linear regression and Pearson’s correlation analysis, the slope was 1.07, close to 1, and the correlation coefficient was 0.813, indicating that the manual scoring and automatic cell detection results were near identical (Fig. 5C). Further, we have presented the model-predicted and manually scored cell counts according to the control (saline) and MPTP groups. Using both methods, the cell counts were significantly different between the control and MPTP groups (p<0.0001), and the distribution of model-predicted and manual counting results was similar within each group (Fig. 5D).

Finally, we evaluated the performance of the proposed algorithm based on three metrics: recall (78.07%), precision (74.46%), and F1 score (76.51%). The proposed algorithm demonstrated superior performance compared to three conventional target detection methods across all evaluation criteria (Table 4). Furthermore, it outperformed commonly utilized image analysis tools such as IJ, CP, Ila, and QuPath. In addition, our model required 2 min on average to count the neurons in an image, indicating satisfactory performance of the proposed algorithm.

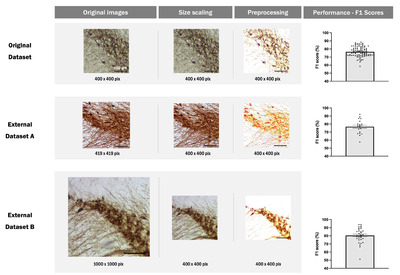

DAB-stained IHC images exhibit variability in staining patterns and image quality due to differences in microscopy equipment and sample magnification dependent on laboratory protocols. Assessing the general applicability of a model to such heterogeneous data is a crucial metric for evaluating its practical utility. To ascertain the generalizability of our model, we applied it to external datasets acquired from other laboratories without additional training. Fig. 6 shows that our model exhibits satisfactory performance (0.77 for external dataset A, 0.80 for external dataset B) when analyzing external datasets. This finding has not been reported in other comparable studies and demonstrates the practical utility and generalizability of our model.

GUI

Given the difficulties in the practical application of the previously proposed algorithms, dopaminergic neurons in SNc are counted manually even today. In this context, to enhance the practicality and usability of our proposed algorithm, we designed an easy-to-use GUI (Fig. 7). Our program supports most image extensions, and users can easily move and resize the image on the program. Additionally, we have provided the function to instantly modify key hyperparameters to account for data diversity. For instance, the user can designate a region of interest on the image using the drawing tool, and the binarize threshold and cell size threshold, which determine the sensitivity of prediction, can be adjusted. Finally, marking can be easily modified for cell counting. Users can delete the marking by clicking the right mouse button or add a new marking by clicking the left mouse button.

Should present the experimental findings in tables or figures, but simple findings can be mentioned directly in the text. Only results necessary to establish the main points of the manuscript should be included. Numerical data should be analyzed using appropriate statistical tests.

DISCUSSION

Quantitative analysis of TH+ cells in the SNc region is an essential step in the verification of animal models of PD. However, since SNc has a high density of neurons, it is difficult to distinguish cells on IHC images. This increases the difficulty of analysis, requiring extensive time and labor for manual quantification, and above all, lacking objectivity. Therefore, an objective measurement method specialized in the SNc region must be urgently developed. Therefore, in the present study, we developed a cell detection algorithm using CNN and provided a user-friendly GUI for the ease of practical application. Two skilled experimenters marked the positions of TH+ cell bodies in SNc in the MPTP and control (saline) groups. Then, pixels corresponding to TH+ cells were predicted using the CNN model, and blobs large enough to be cells were counted. The proposed algorithm achieved a prominent F1 score (76.51%) when quantifying the consistency of cell position and presence with the human-set ground truth. In addition, model reliability was demonstrated by distinguishing the MPTP group from the control group (p<0.0001).

In this study, we introduced a customized CNN model. While up-to-date model architectures such as VGG16 and MobileNet can be utilized for classification tasks, we discovered that their application resulted in lower accuracy compared to our customized CNN model. This may be due to the larger crop size required by up-to-date architectures and the fact that the pretraining image data is from a different domain than the images used in our study. As a result, we opted for a customized CNN model and fine-tuned the crop size and hyperparameters to optimize performance.

We compared the classification performance of the proposed method compared with that of other conventional methods. Using our IHC image dataset, we analyzed the cell detection performance of three conventional image-processing methods, including LoG [15], DoG [17], and DoH [20]. Our proposed method showed significantly better performance than the three conventional image-processing methods (Table 4). The CNN-based deep learning method performs the analysis through more diverse features than the conventional methods [44]. Specifically, the conventional methods use only a single feature; thus, the target of analysis is limited to circular cells with clear boundaries from the background [45]. However, TH+ cells in the SNc region have various shapes and vague boundaries from the background. For instance, neuronal dendrites and axons as well as neuronal clustering vary the cell shape (Fig. 4), rendering it difficult to distinguish them from the background. Overall, because of these complexities of IHC results, our CNN-based deep learning model outperformed the conventional methods.

IJ, CP, Ila, and QP are the most popular free image analysis software that allow automatic cell detecting on an image [24]. Although these software programs are considered to be somewhat accurate and precise in detection, they are insufficient for application to analyze images used in the present study due to the characteristics of TH+ neurons in the SNc region of IHC images. In this study, we used each image analysis software to segment our dataset by following the objective analysis procedure. However, as shown in Table 4, the image analysis software performed worse than our model. Specifically, IJ and CP require users to adjust numeric parameters for detection [46]. While IJ provides a simple workflow with two parameters, size and circularity [47], most cell bodies on IHC images are neglected even though the ranges of parameters are set to the maximum and appropriate boundaries of the detected cell bodies cannot be obtained when using IJ. Additionally, while our GUI allows users to edit the detection results simply by clicking on the image, modifying the result in IJ requires many steps [46]. Unlike IJ, CP offers numerous parameters in the “Advanced Settings” section [48]. To examine the results after changing the parameters, users must click the “Analyze Images” button and wait for approximately 1 min for each change. Thus, manually optimizing the parameters is challenging. In addition, CP shows poor performance in distinguishing between cell boundaries and background noises [46]. Overall, both IJ and CP have disadvantages associated with their parameters and difficulties in segmenting cells with unclear boundaries and troubleshooting the errors. Ila and QP are machine learning-based software requiring users to annotate cell-positive and cell-negative areas [49, 50]. Ila can provide prediction results rapidly based on annotations by users [51]. However, it shows inadequate performance in segmentation, particularly between the neighboring cell bodies. QP has the most user-friendly interface and the best detection performance among the four software [24]. Nonetheless, it presents many false positives and its performance cannot be improved even after adjusting the parameters and training with some annotations. Meanwhile, although Ila and QP have a better GUI and performance than IJ and CP, they still lack segmentation and classification accuracy [50, 52], due perhaps to the absence of CNN application. To achieve reliable outcomes using Ila and QP, manual annotation and modification by adequately experienced and trained scientists appear essential, because the accuracy of analytical results closely depends on cell classification and selection thresholds [51, 52]. Hence, our proposed algorithm outperformed the four existing tools, with less manual adjustment when analyzing the IHC images with many background noises and dense cell bodies used in PD.

Although two valuable previous studies have applied CNN-based deep learning models for TH+ cell detection [36, 37], their datasets or methods are not accessible. Moreover, F1 scores using conventional methods vary across studies, indicating that the datasets among works are not uniform. Consequently, direct comparison with previous studies is limited. Nonetheless, the present study has strengths because we provide a freely accessible user-friendly interface, which the other studies do not. If the datasets of each study are shared, proper comparison among deep learning models will be possible. Moreover, data sharing will render deep learning models more powerful due to the availability of more training data. Therefore, we have published all IHC image data and annotation information on OSF to contribute to future studies.

For practical applications, the generalizability of models is critical. In this study, we tested the proposed model on IHC samples from different laboratories to demonstrate its generalizability. These new datasets differed in terms of IHC protocols and imaging equipment and contained 20 and 32 images respectively. We tested the model on these datasets without retraining. Despite variations in experimental conditions, our model showed good performance with average F1 scores of 0.77 and 0.80 respectively after resizing the images using a Python image processing library. This demonstrates the robustness and adaptability of our model in handling variations in experimental conditions. Such validation of generalizability to external datasets has not been presented in similar studies, highlighting the superiority of our approach in developing a widely applicable cell detection algorithm.

Furthermore, our model could generate false-positive errors, which usually appear at sites of foreign bodies or damaged tissue during the IHC staining process. Although foreign bodies or tissue damaging are not intended by experimenters, they often occur in IHC experiments in practical situations. This problem may be solved by designating a polygon-shaped region of interest, which is provided in the GUI. Typically, false-negative errors appear when the color of the patches is very bright, regardless of the cell-shaped morphology. This may be caused by the imbalance of intensity on the image due to the lack of quality control in the DAB staining process. However, since deep learning models do not use the brightness feature alone for classification, this problem may be improved by the accumulation of training data.

Finally, our intuitive interface provides a better user experience than the conventional tools in several aspects. First, since our GUI automatically adjusts the brightness and contrast while allowing manual modification, users do not need to apply other programs for image processing. Next, in our GUI, users can immediately compare the original image and detection results in the same window. In addition, users need not conduct manual annotation and manage numerous parameters. Our CNN-based model suggests a promising result without considerable adjustment. Moreover, users can precisely adjust two parameters, classification and cell size threshold, and immediately receive visualized feedback on the modification, enabling optimized parameter setting. Additionally, users can easily save the detection outcomes in a comprehensible and usable form. Finally, users can obtain coordinates of the markers as a CSV file and any image displayed on the window as a JPG file. These features of our GUI will allow anyone to utilize it with little practice. We are considering realizing a GUI on the Web to increase its usability and improve the performance of the algorithm.

Our GUI includes functions that allow users to adjust the classification threshold and minimum cell size threshold. We recommend using the default value of 0.5 for the classification threshold. However, if desired, the threshold can be adjusted according to the user’s preference before the final manual check. For example, setting the threshold high will eliminate ambiguous cells, which can be added back at the user’s discretion and vice versa. The recommended minimum cell size threshold for the SNc and VTA regions is 136, based on our dataset. The appropriate cell size threshold may vary depending on the observed brain region. All parameters are reflected in real-time in the GUI, allowing users to use this feedback to set the parameters.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

All data and codes associated with the present study are available at OSF (https://osf.io/js8nd/) or GitHub repository (https://github.com/KHUSKlab/pd_mouse_cell_detection).

Figures

Tables

Details of the internal dataset

| Mouse | Group | Images | Average cell counts |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saline | 8 | 102.750 |

| 2 | Saline | 8 | 103.875 |

| 3 | Saline | 8 | 109.500 |

| 4 | Saline | 8 | 100.875 |

| 5 | Saline | 8 | 91.000 |

| 6 | Saline | 8 | 85.250 |

| 7 | Saline | 4 | 112.750 |

| 8 | MPTP | 8 | 82.500 |

| 9 | MPTP | 8 | 75.500 |

| 10 | MPTP | 8 | 81.125 |

| 11 | MPTP | 8 | 73.500 |

| 12 | MPTP | 8 | 80.250 |

| 13 | MPTP | 4 | 80.250 |

A total of 96 images, with 52 images from the control (saline) group and 44 images from the MPTP group, were acquired from 13 mice. On average, there were 100.8 cells in control images and 78.8 cells in MPTP images.

Details of the entire dataset

| Dataset | Images | Magnification | Average cell counts | Spatial resolution (μm/pixel) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | 96 | 40× | 100.800 | 0.924 |

| External A | 20 | 40× | 120.700 | 0.881 |

| External B | 32 | 100× | 141.200 | 0.369 |

The original dataset was used for both training and cross-validation of the model. The external datasets were from different laboratories where different IHC staining protocols are conducted, and they were used only for testing the generalization ability of the model.

CNN model structure details

| Layer | Input | Ouput | Filter size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conv2D (ReLU) | 28×28×27 | 25×25×256 | 4×4 |

| MaxPolling2D | 25×25×256 | 12×12×256 | 2×2 |

| Conv2D (ReLU) | 12×12×256 | 10×10×256 | 3×3 |

| MaxPolling2D | 10×10×256 | 5×5×256 | 2×2 |

| Conv2D (ReLU) | 5×5×256 | 4×4×256 | 2×2 |

| MaxPolling2D | 4×4×256 | 2×2×256 | 2×2 |

| Flatten | 2×2×256 | 1,024 | |

| Dense (ReLU) | 1,024 | 128 | 1 |

| Dense (ReLU) | 128 | 128 | 1 |

| Dense (ReLU) | 128 | 128 | 1 |

| Dense (ReLU) | 128 | 64 | 1 |

| Dense (ReLU) | 64 | 64 | 1 |

| Dense (ReLU) | 64 | 64 | 1 |

| Dense (sigmoid) | 64 | 64 | 1 |

| Dense (softmax) | 64 | 2 | 1 |

The type, shape of input and output, and filter size of each layer are indicated. ReLU was used as the activation function for convolutional layers and most of the dense layers. Sigmoid and softmax functions were applied for the last two dense layers, respectively.

Comparison of detection performance between the proposed algorithm with conventional target detection methods and other image analysis tools

| Method | TP | FP | FN | Recall | Precision | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed algorithm | 6745 | 3557 | 1751 | 79.26% | 68.97% | 73.00% |

| LoG | 6064 | 8030 | 2432 | 71.02% | 54.01% | 56.46% |

| DoG | 6619 | 17358 | 1877 | 78.15% | 33.79% | 45.24% |

| DoH | 7984 | 26125 | 512 | 93.80% | 28.82% | 42.31% |

| ImageJ | 4473 | 6142 | 4023 | 52.65% | 51.42% | 47.42% |

| ilastik | 2464 | 765 | 6032 | 28.13% | 80.83% | 37.22% |

| QuPath | 3899 | 3008 | 4597 | 45.98% | 63.74% | 48.79% |

True positive (TP), false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) with averages of recall, precision, and F1 score of images using the respective methods. Our CNN-based TH+ dopaminergic neuron detection algorithm showed better performance than three conventional target detection methods: Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG), difference of Gaussian (DoG), and determinant of Hessian (DoH), and three image analysis tools: ImageJ, ilastik, and QuPath. Cellprofiler was excluded due to lack of detection performance, therefore not quantifiable. In this table, the F1 score for the proposed algorithm is not 76.51%, but 73.00%. This is because the F1 score was calculated for all images instead of the average for individual images.

References

- Armstrong MJ, Okun MS (2020) Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: a review. JAMA 323:548-560

- Hanagasi HA, Akat S, Gurvit H, Yazici J, Emre M (2011) Pain is common in Parkinson's disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 113:11-13

- Klietz M, Tulke A, Müschen LH, Paracka L, Schrader C, Dressler DW, Wegner F (2018) Impaired quality of life and need for palliative care in a German cohort of advanced Parkinson's disease patients. Front Neurol 9:120

- Fall PA, Saleh A, Fredrickson M, Olsson JE, Granérus AK (2003) Survival time, mortality, and cause of death in elderly patients with Parkinson's disease: a 9-year follow-up. Mov Disord 18:1312-1316

- Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA (2013) Incidence and pathology of synucleinopathies and tauopathies related to parkinsonism. JAMA Neurol 70:859-866

- Betarbet R, Sherer TB, Greenamyre JT (2002) Animal models of Parkinson's disease. Bioessays 24:308-318

- Kurosaki R, Muramatsu Y, Kato H, Araki T (2004) Biochemical, behavioral and immunohistochemical alterations in MPTP-treated mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 78:143-153

- White RB, Thomas MG (2012) Moving beyond tyrosine hydroxylase to define dopaminergic neurons for use in cell replacement therapies for Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 11:340-349

- Ip CW, Cheong D, Volkmann J (2017) Stereological estimation of dopaminergic neuron number in the mouse substantia nigra using the optical fractionator and standard microscopy equipment. J Vis Exp 127:56103

- Hwang TY, Song MA, Ahn S, Oh JY, Kim DH, Liu QF, Lee W, Hong J, Jeon S, Park HJ (2019) Effects of combined treatment with acupuncture and Chunggan formula in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2019:3612587

- Brey EM, Lalani Z, Johnston C, Wong M, McIntire LV, Duke PJ, Patrick CW Jr (2003) Automated selection of DAB-labeled tissue for immunohistochemical quantification. J Histochem Cytochem 51:575-584

- Coventry BJ, Neoh SH, Mantzioris BX, Skinner JM, Zola H, Bradley J (1994) A comparison of the sensitivity of immunoperoxidase staining methods with high-sensitivity fluorescence flow cytometry-antibody quantitation on the cell surface. J Histochem Cytochem 42:1143-1147

- Gonda K, Watanabe M, Tada H, Miyashita M, Takahashi-Aoyama Y, Kamei T, Ishida T, Usami S, Hirakawa H, Kakugawa Y, Hamanaka Y, Yoshida R, Furuta A, Okada H, Goda H, Negishi H, Takanashi K, Takahashi M, Ozaki Y, Yoshihara Y, Nakano Y, Ohuchi N (2017) Quantitative diagnostic imaging of cancer tissues by using phosphor-integrated dots with ultra-high brightness. Sci Rep 7:7509

- Rabey JM, Hefti F (1990) Neuromelanin synthesis in rat and human substantia nigra. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect 2:1-14

- Lindeberg T (1998) Feature detection with automatic scale selection. Int J Comput Vis 30:79-116

- Gonzalez RC, Woods RE, Eddins SL (2020) Digital image processing using MATLAB. 3rd ed. Gatesmark Publishing, Knoxville, TN

- Lowe DG (2004) Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int J Comput Vis 60:91-110

- Mikolajczyk K, Schmid C (2004) Scale & affine invariant interest point detectors. Int J Comput Vis 60:63-86

- Mikolajczyk K, Schmid C (2005) Performance evaluation of local descriptors. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 27:1615-1630

- Bay H, Ess A, Tuytelaars T, Gool LV (2008) Speeded-up robust features (SURF). Comput Vis Image Underst 110:346-359

- Razlighi QR, Stern Y (2011) Blob-like feature extraction and matching for brain MR images. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011:7799-7802

- Saien S, Hamid Pilevar A, Abrishami Moghaddam H (2014) Refinement of lung nodule candidates based on local geometric shape analysis and Laplacian of Gaussian kernels. Comput Biol Med 54:188-198

- Huang YH, Chang YC, Huang CS, Chen JH, Chang RF (2014) Computerized breast mass detection using multi-scale Hessian-based analysis for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. J Digit Imaging 27:649-660

- Sanka I, Bartkova S, Pata P, Smolander OP, Scheler O (2021) Investigation of different free image analysis software for high-throughput droplet detection. ACS Omega 6:22625-22634

- González JE, Radl A, Romero I, Barquinero JF, García O, Di Giorgio M (2016) Automatic detection of mitosis and nuclei from cytogenetic images by CellProfiler software for Mitotic index estimation. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 172:218-222

- O'Brien J, Hayder H, Peng C (2016) Automated quantification and analysis of cell counting procedures using ImageJ plugins. J Vis Exp 117:54719

- Yu G, Yu C, Xie F, He M (2022) Automated tumor count for Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index determination in neuroblastoma using whole slide image and Qupath, an image analytic software. Pediatr Dev Pathol 25:526-537

- Li C, Ma X, Deng J, Li J, Liu Y, Zhu X, Liu J, Zhang P (2021) Machine learning-based automated fungal cell counting under a complicated background with ilastik and ImageJ. Eng Life Sci 21:769-777

- Song JH, Choi W, Song YH, Kim JH, Jeong D, Lee SH, Paik SB (2020) Precise mapping of single neurons by calibrated 3D reconstruction of brain slices reveals topographic projection in mouse visual cortex. Cell Rep 31:107682

- Khan ZH, Mohapatra SK, Khodiar PK, Ragu Kumar SN (1998) Artificial neural network and medicine. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 42:321-342

- Lecun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, Haffner P (1998) Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE 86:2278-2324

- LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G (2015) Deep learning. Nature 521:436-444

- Anwar SM, Majid M, Qayyum A, Awais M, Alnowami M, Khan MK (2018) Medical image analysis using convolutional neural networks: a review. J Med Syst 42:226

- Febrianto DC, Soesanti I, Nugroho HA (2020) Convolutional neural network for brain tumor detection. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 771:012031

- Jiao H, Jiang X, Pang Z, Lin X, Huang Y, Li L (2020) Deep convolutional neural networks-based automatic breast segmentation and mass detection in DCE-MRI. Comput Math Methods Med 2020:2413706

- Penttinen AM, Parkkinen I, Blom S, Kopra J, Andressoo JO, Pitkänen K, Voutilainen MH, Saarma M, Airavaara M (2018) Implementation of deep neural networks to count dopamine neurons in substantia nigra. Eur J Neurosci 48:2354-2361

- Zhao S, Wu K, Gu C, Pu X, Guan X (2018). SNc neuron detection method based on deep learning for efficacy evaluation of anti-PD drugs. 2018 Annual American Control Conference (ACC). 1981-1986

- Montero T, Gatica RI, Farassat N, Meza R, González-Cabrera C, Roeper J, Henny P (2021) Dendritic architecture predicts in vivo firing pattern in mouse ventral tegmental area and substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Front Neural Circuits 15:769342

- Ardah MT, Bharathan G, Kitada T, Haque ME (2020) Ellagic acid prevents dopamine neuron degeneration from oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in MPTP model of Parkinson's disease. Biomolecules 10:1519

- Zhu G, Harischandra DS, Ghaisas S, Zhang P, Prall W, Huang L, Maghames C, Guo L, Luna E, Mack KL, Torrente MP, Luk KC, Shorter J, Yang X (2020) TRIM11 prevents and reverses protein aggregation and rescues a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Cell Rep 33:108418

- Su CF, Jiang L, Zhang XW, Iyaswamy A, Li M (2021) Resveratrol in rodent models of Parkinson's disease: a systematic review of experimental studies. Front Pharmacol 12:644219

- Leem YH, Park JS, Park JE, Kim DY, Kim HS (2022) Neurogenic effects of rotarod walking exercise in subventricular zone, subgranular zone, and substantia nigra in MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease mice. Sci Rep 12:10544

- Versaux-Botteri C, Nguyen-Legros J, Vigny A, Raoux N (1984) Morphology, density and distribution of tyrosine hydroxylase-like immunoreactive cells in the retina of mice. Brain Res 301:192-197

- Valueva MV, Nagornov NN, Lyakhov PA, Valuev GV, Chervyakov NI (2020) Application of the residue number system to reduce hardware costs of the convolutional neural network implementation. Math Comput Simul 177:232-243

- Parvathi SSL, Jonnadula H (2021) A comprehensive survey on medical image blob detection and classification models. In: 2021 International Conference on Advancements in Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computing and Automation (ICAECA) pp 1-6. IEEE, Piscataway, NJ.

- Dobson ETA, Cimini B, Klemm AH, Wählby C, Carpenter AE, Eliceiri KW (2021) ImageJ and CellProfiler: complements in open-source bioimage analysis. Curr Protoc 1:e89

- Grishagin IV (2015) Automatic cell counting with ImageJ. Anal Biochem 473:63-65

- Stirling DR, Swain-Bowden MJ, Lucas AM, Carpenter AE, Cimini BA, Goodman A (2021) CellProfiler 4: improvements in speed, utility and usability. BMC Bioinformatics 22:433

- Bankhead P, Loughrey MB, Fernández JA, Dombrowski Y, McArt DG, Dunne PD, McQuaid S, Gray RT, Murray LJ, Coleman HG, James JA, Salto-Tellez M, Hamilton PW (2017) QuPath: open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci Rep 7:16878

- Berg S, Kutra D, Kroeger T, Straehle CN, Kausler BX, Haubold C, Schiegg M, Ales J, Beier T, Rudy M, Eren K, Cervantes JI, Xu B, Beuttenmueller F, Wolny A, Zhang C, Koethe U, Hamprecht FA, Kreshuk A (2019) ilastik: interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat Methods 16:1226-1232

- Kreshuk A, Zhang C (2019) Machine learning: advanced image segmentation using ilastik. Methods Mol Biol 2040:449-463

- Loughrey MB, Bankhead P, Coleman HG, Hagan RS, Craig S, McCorry AMB, Gray RT, McQuaid S, Dunne PD, Hamilton PW, James JA, Salto-Tellez M (2018) Validation of the systematic scoring of immunohistochemically stained tumour tissue microarrays using QuPath digital image analysis. Histopathology 73:327-338